Holly Waddington’s Visual Symphony of Victorian Elegance and Modern Intricacy

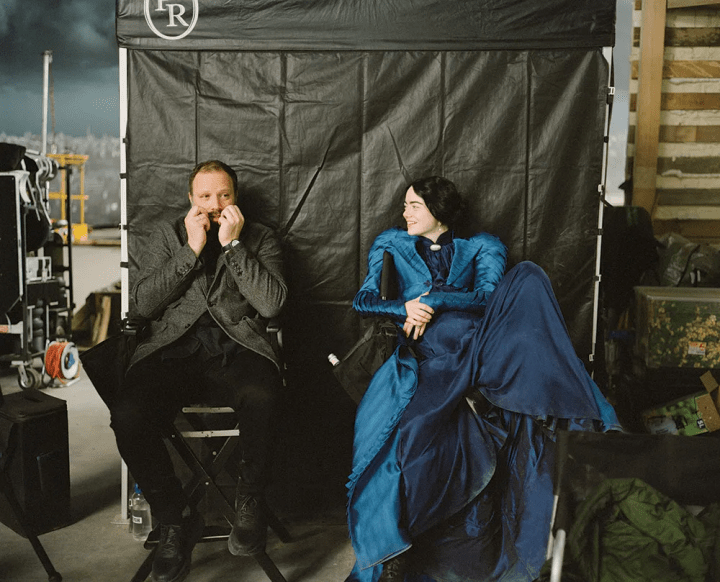

In “Poor Things,” Holly Waddington, a seasoned costume designer renowned for her work in acclaimed period productions like “The Great” and “Lady Macbeth,” elevates her craft to new heights. Waddington masterfully weaves a visual narrative, transcending chronological constraints by infusing Victorian stylistic codes with a contemporary flair. Drawing inspiration from Egon Schiele’s art, she orchestrates a symphony of colors and silhouettes that mirror the protagonist Bella Baxter’s (Emma Stone) evolution. Each act unfolds with precision, echoing the profound impact of Bella’s transformative journey, from the nuanced influences of Schiele’s artistry to the avant-garde designs of Courréges. Waddington’s artistic finesse not only captivates but immerses the audience in the immediacy of the story, underscoring the potent synergy between costume and narrative in this cinematic masterpiece by Yorgos Lanthimos.

“Poor Things!” unfolds as a whimsical sci-fi spectacle against the backdrop of late 1800s, seamlessly blending echoes of Frankenstein with the fervor of women’s sexual and political liberation. At the heart of this enchanting “fairy tale” lies the extraordinary life of Bella, a woman resurrected from a suicide attempt by the eccentric Dr. Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe), who ingeniously replaces her brain with that of her unborn child.

In the film’s early pages, Bella emerges as an infant figure, draped in nightgowns and white baby doll dresses, whimsically navigating the rooms of her London upbringing. A bustle cage, reminiscent of a mermaid’s tail, captures the playful essence of the era’s silhouettes. Bare legs, bare feet, and cascading loose or braided hair embody her innocence.

The transition from black and white to a burst of color coincides with Bella’s arrival in Lisbon, where freedom and sexuality unfurl before her. Freed from the constraints of a governess dictating her attire, Bella ventures into the city clad in canary yellow shorts and a frilly white blouse. Waddington’s ingenious touch manifests in ankle-length white boots inspired by Courrèges’ space-age aesthetic of the ’60s. The top and shorts, termed “modesty pieces” in the Victorian era, defy societal norms, covering skin deemed provocative even in ankle exposure.

As Waddington reveals in an interview, Bella’s Portuguese wardrobe mirrors her youthful rebellion against societal impositions. Duncan Wedderburn, her lover, begrudgingly witnesses her newfound spirit of independence, culminating in a restaurant scene where Bella, adorned in the film’s brightest yellow, dons a dress embellished with oversized bows. This sartorial choice symbolizes Bella’s defiance, overshadowing conventions with her vivid presence, as she navigates the complexities of self-exploration and challenges societal expectations with grace and audacity.

As Bella embarks on a transformative journey aboard the ship to Greece, her wardrobe becomes the canvas of an emotional metamorphosis. Confronting the harsh realities of poverty and injustice, the innocence of her childhood reemerges in the guise of a refined woman’s ensemble, symbolizing a poignant return to her roots.

Lying on her bed, enveloped in a glimmer of innocence, Bella’s bewildered expression mirrors the profound impact of an encounter with an older woman and a supportive friend. This pivotal moment unfolds as they introduce her to the realms of literature, philosophy, and critical thinking, catalyzing a remarkable transformation. The audience bears witness to Bella’s evolution from a vulnerable young girl, ensnared by life’s challenges and a possessive man, into a cultivated and educated woman.

Her clothing becomes a narrative in itself, mirroring her growth and maturity. Even in Paris, where she spends nearly as much time disrobed as clothed, her attire undergoes a dynamic evolution. Following her break from Wedderburn, Bella chooses an unconventional path, entering the realm of a brothel. In scenes depicting her career as a prostitute, her garments embrace pastel hues—light pinks and translucent fabrics—a tribute to the female form.

Notably, Waddington introduces an anachronistic clash between fabric and form by incorporating latex into the creation of a striking yellow raincoat. This inventive touch draws inspiration from Victorian-era condoms, infusing a layer of irony into a pivotal turning point in the film’s plot. In this nuanced exploration of Bella’s journey, the interplay between clothing, colors, and unconventional materials serves as a visual tapestry, capturing the essence of her empowerment and defiance in the face of societal norms.

Emma Stone’s portrayal of Bella in “Poor Things” boldly defies the conventions of Victorian costume, challenging norms and embodying a spirit of nonconformity. Notably, even in ostensibly serious settings like socialist meetings and medical school, Bella’s attire—a dark coat with balloon sleeves and black boots with a chunky heel—subverts expectations by leaving her legs exposed.

Traditional attire only briefly graces the screen when she is still Victoria, teetering on the precipice of her demise, or during her brief kidnapping in the house of her ex-husband. Throughout the film, the costumes crafted by designer Waddington meticulously mirror the emotional and cognitive nuances of Bella’s journey. Inspired by the vibrant set colors and the protagonist’s tenacity and intelligence, the costumes become a dynamic storytelling element, actively shaping Yorgos Lanthimos’s narrative.

In “Poor Things,” Waddington’s designs transcend mere aesthetics, serving as a powerful means of communication that parallels the impact of the script. This synergy underscores a profound truth—both on and off-screen—that women’s liberation is a holistic journey involving not only the body but also the mind. In weaving this intricate tapestry of defiance and resilience, the film eloquently asserts that the essence of liberation is found in the convergence of intellect and expression.