“The Intersection of Tradition and Avant-Garde in Men’s Fashion”

Menswear is a realm of understated elegance and impeccable taste, as passionately endorsed by Lee McQueen in his assertion that it’s all about “good style and good taste.” However, these deceptively simple words conceal the intricate tapestry of McQueen’s creative odyssey.

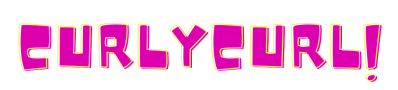

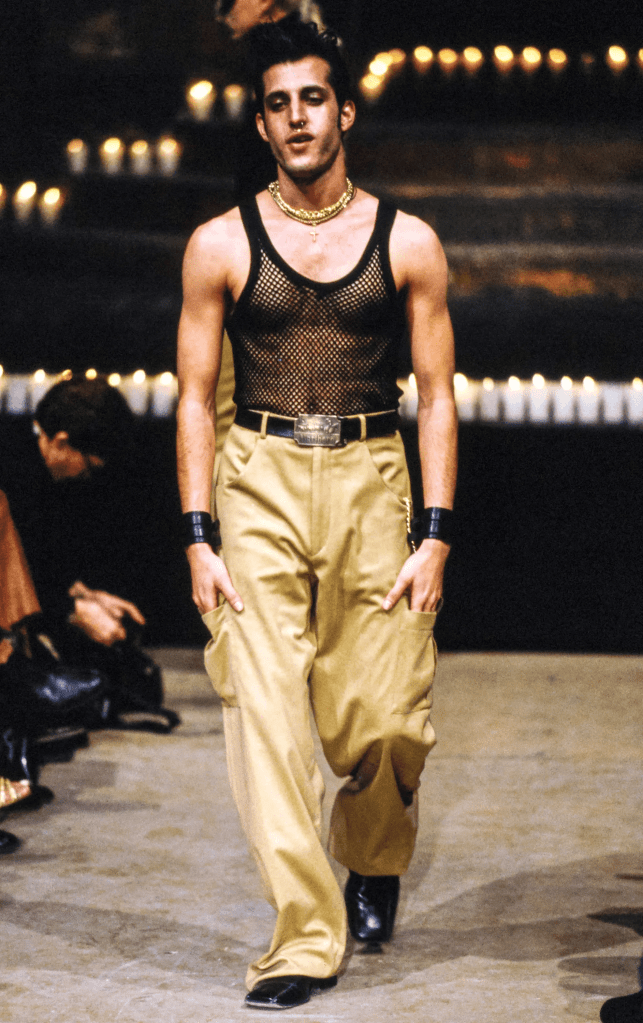

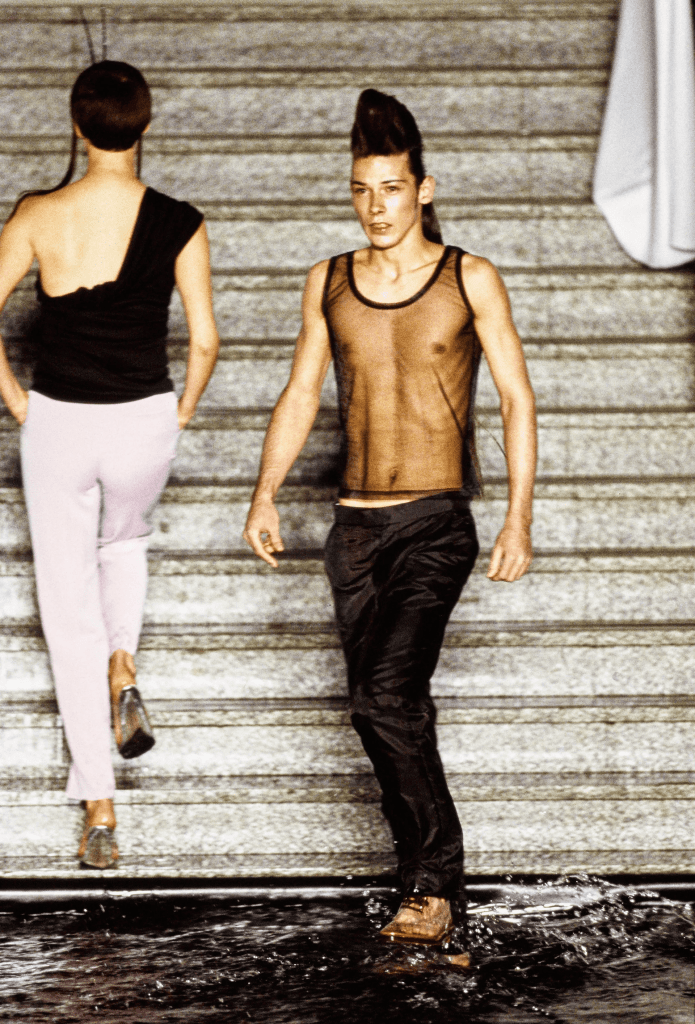

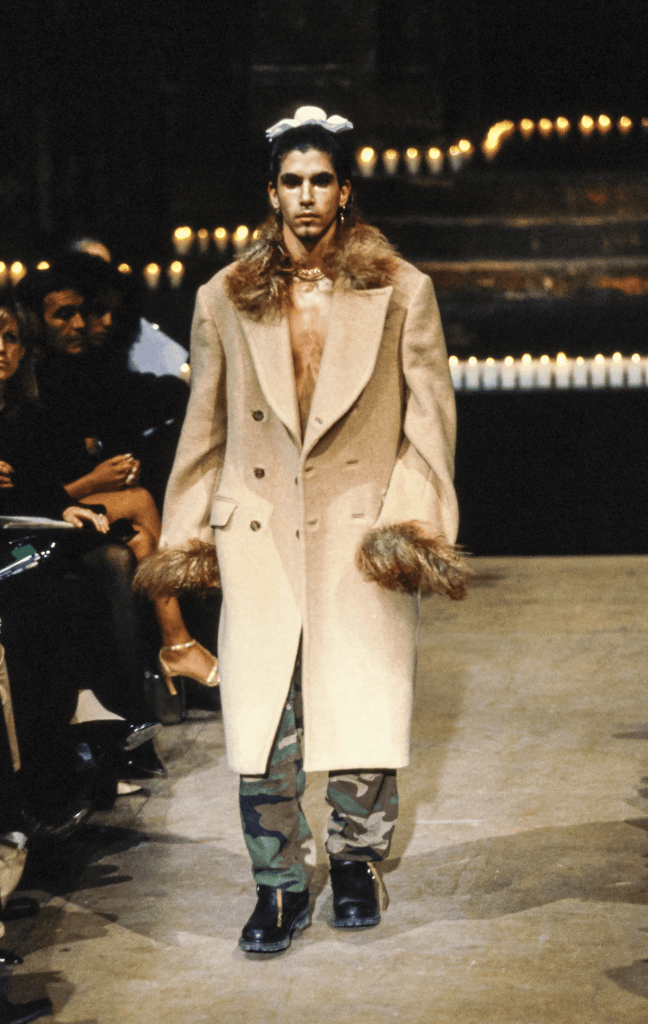

In his pursuit of fashion that would strike fear into the hearts of those who beheld it on women, McQueen’s approach to men’s attire diverged significantly. For men, he aspired not only to dismantle the established norms but also to safeguard the timeless traditions. This juxtaposition is most evident in the collections spanning from 1996 to 1998, where, though a minority, McQueen’s male designs seamlessly extended the daring frontiers of women’s fashion.

Fast forward to 2004 when McQueen boldly entered the arena of men’s fashion, making his debut at Milan Fashion Week. Yet, the spotlight remained stubbornly fixed on his women’s collections. Only with the brand’s meteoric rise to prominence, and following McQueen’s untimely departure in February 2010, did both the men’s and women’s lines converge onto a shared, commercially accessible idiom. Before this pivotal moment, McQueen’s ‘canonical’ creations were unequivocally associated with women’s fashion.

Yet, one must delve deeper into McQueen’s formative years spent amidst the hallowed ateliers of Savile Row. Here, he apprenticed under venerable tailoring houses such as Anderson & Sheppard and Gieves & Hawkes, artisans renowned for crafting garments fit for royalty, including the likes of King Charles III. A notable anecdote recounts McQueen stitching the audacious phrase ‘I am a cunt’ into the lining of a jacket for the reigning King Charles III. This dual narrative underscores the idea that while women’s fashion provided a canvas for artistic exploration and escape, McQueen’s approach to men’s attire was profoundly anchored in his own life story—a journey deeply entwined with the fragile complexities of romance.

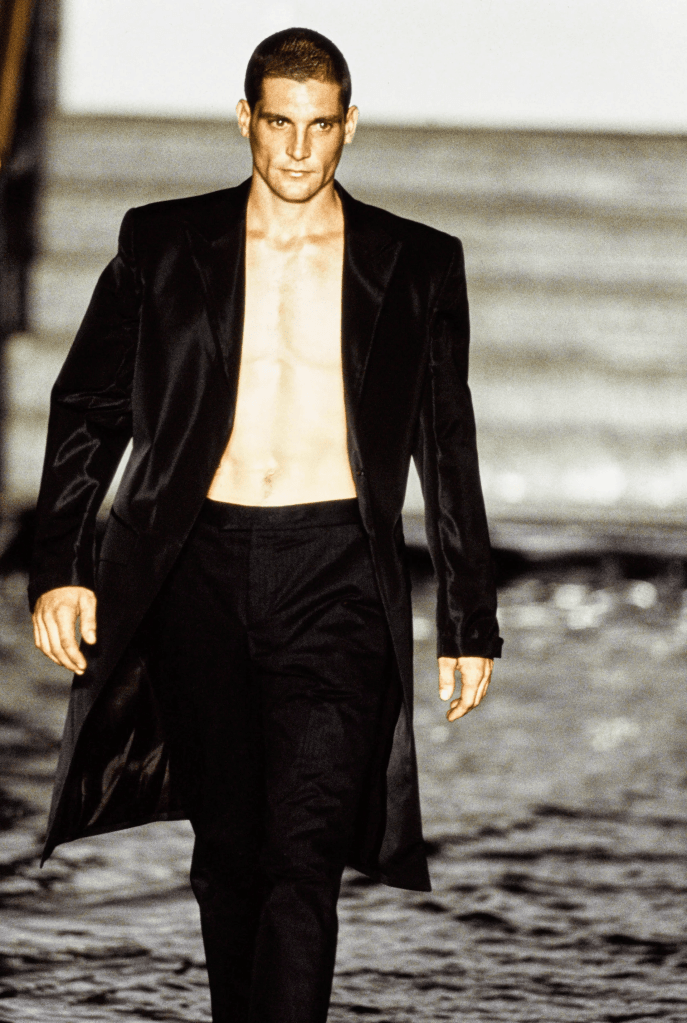

Lee McQueen’s exploration of masculinity was a nuanced departure from convention. While his designs exuded masculinity, it was within the realm of tailoring that his innovations lay concealed. His foray into menswear commenced with a collection of twelve bespoke ensembles, a collaborative effort with H. Huntsman & Sons, lauded as Savile Row’s preeminent tailors. Vogue, in a July 2002 feature, described these suits as featuring “narrow waists, broader lapels, and embellishments like gold buttons, pink and yellow diamond tie pins, and cufflinks.”

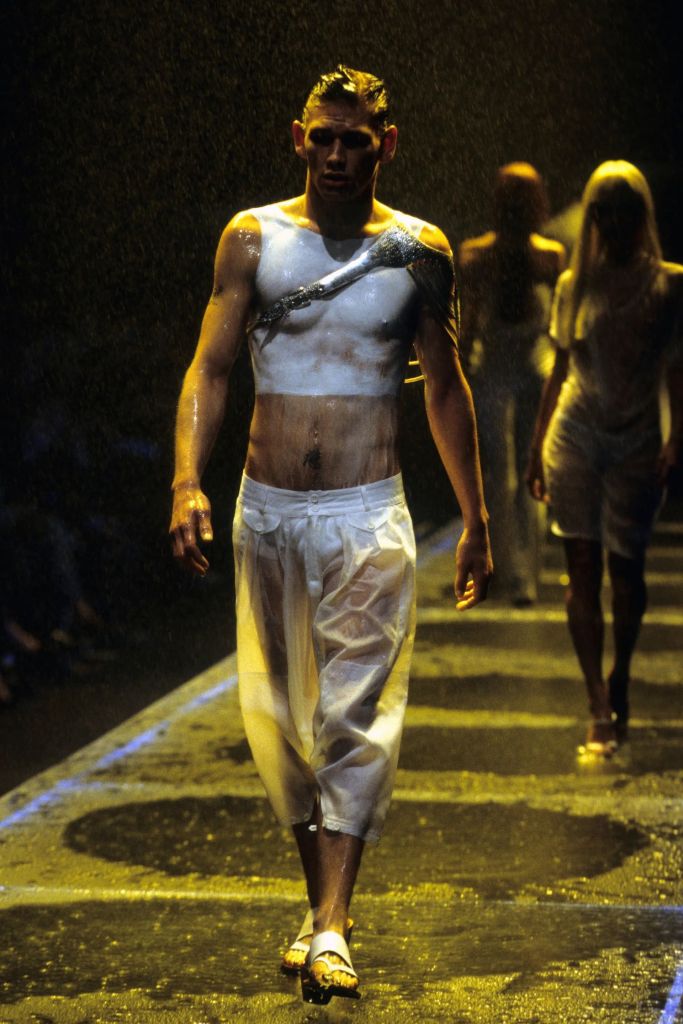

Yet, beneath the surface, a more overt subversion occasionally emerged, notably in the Spring/Summer 1998 show. Here, men confidently adorned corsets and flip-flops with slight heels, challenging established gender norms. However, the true sartorial expression of queerness often resided within the tailoring, subtly eluding immediate notice.

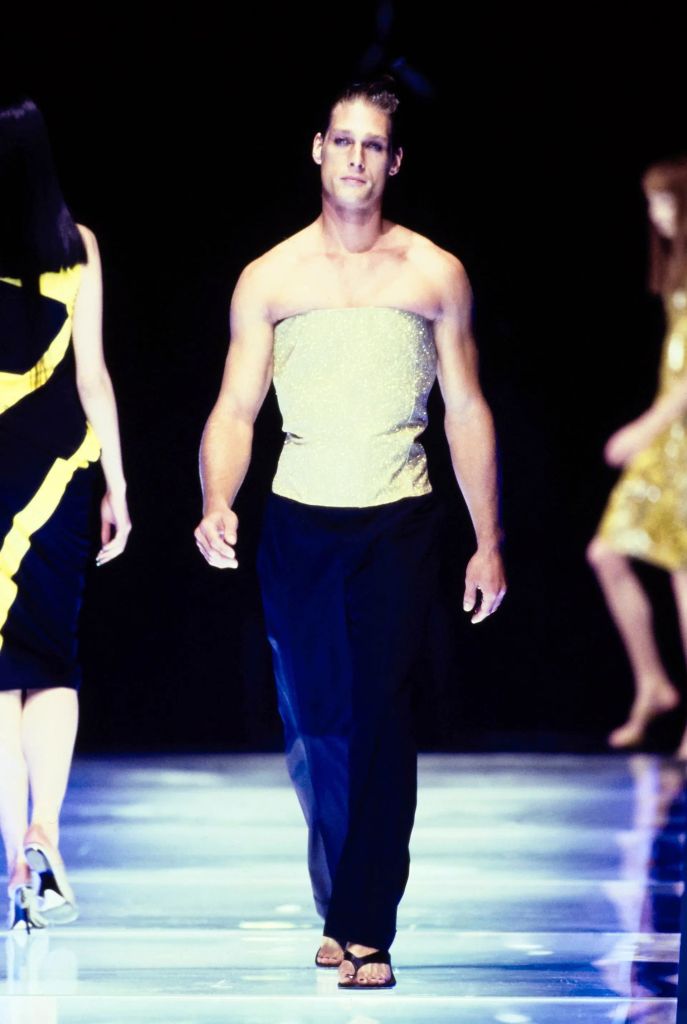

When we contemplate McQueen’s menswear creations today, only a portion of their structural and semantic complexity becomes apparent. These suits may seem like conventional attire at first glance, yet intricate details remain concealed. Think of cardigans discreetly adorned with sequins, leather welts discreetly encasing the hems of jumpers, traditionally masculine trousers featuring a curiously low waistline, and fur accents embellishing the sleeves and collars of men’s coats. McQueen’s genius lay in crafting menswear that challenged norms and beckoned us to look deeper, beyond the surface.

Two decades ago, in a 2003 online Q&A featured on SHOWstudio, McQueen found himself at the intersection of a shifting menswear landscape. A pointed question surfaced: Why did menswear increasingly adopt the vibrant diversity, colors, and styles akin to womenswear? In response, McQueen delved into the essence of menswear, emphasizing that it was fundamentally shaped by men themselves. He astutely recognized that designing for men presented a unique challenge – a resistant audience that loathed being dictated to, unlike their female counterparts.

Amidst this intriguing discourse, McQueen ingeniously wove the ambiguities and nuances of queerness into the fabric of his designs. These elements remained both incorporated and subtly concealed within the linear elegance of suits. It was evident in the slender shoulders, the artful construction of jackets and trousers that accentuated the graceful curvature of the back and the musculature of the glutes. Seams, pockets, and structural elements converged, directing attention to the pelvic region, while certain suits boasted pagoda shoulders that heightened the profile of the trapezius muscles.

These intricate details formed what could aptly be described as “constellations of contradictory themes,” a term elucidated brilliantly by Icon magazine in their profound analysis titled “Kinky Suits.” This in-depth study peeled back the layers, revealing the sheer technical prowess concealed within McQueen’s work. It illuminated how his designs were not just garments but intricate narratives woven into the very fabric of fashion history.

When we examine these looks through a contemporary lens, they may not conform to our modern understanding of non-binary fashion. However, for Lee McQueen, his menswear was far more than a commentary on sartorial norms. It was a canvas through which he painted his own identity, impressions, and tastes.

In the captivating biography “Alexander McQueen: The Life and the Legacy,” Judith Watt reveals a fascinating evolution. Early ventures into menswear until 2002 were conceived with an ideal customer in mind. Yet, from 2005 onward, McQueen embarked on a remarkable journey, designing with his personal taste as the ultimate compass. As Keri Rowe beautifully articulates in her essay “Elevating the Other,” dedicated to McQueen’s SS06 ‘Killa’ collection, he transitioned from championing the strength of women in his creations to defending his own vulnerabilities through menswear. McQueen frequently stated that his collections were a direct reflection of his own life.

Certain recurring elements punctuated his menswear creations: the classic formal suit, the daring transparency of a top, the sleeveless knits, the audacious corsets, and the opulent baroque embroidery. Yet, the true revolution unfolded in the minutiae of construction—a realm where the designer’s message was intricately concealed, like a whisper beneath the fabric’s surface. In the spirit of the enigmatic message sewn into the lining of King Charles III’s jacket, one could sense it lingering but struggled to fully discern it.

In the heady atmosphere of the 1990s, Karl Lagerfeld astutely observed that McQueen’s fashion sensibilities were “nearer to Damien Hirst than to Givenchy.” This statement alludes to McQueen’s tumultuous tenure as the creative helm of the iconic fashion brand, a period where his work bore the hallmarks of artistic passion and unrelenting obsession, shaping the landscape of fashion in ways both profound and enigmatic.

In the grand tapestry of men’s fashion, much of its storied legacy now lies in the shadows, if not completely forgotten, then certainly eclipsed by the dazzling spectacles gracing the catwalks of women’s collections. Following the untimely passing of McQueen, a new chapter unfolded as Sarah Burton crafted a collection infused with inspiration from historical English attire, a subtle nod to the beloved aesthetics the designer had woven into the public’s consciousness.

Yet, the once-fiery desire to shock had dimmed, and that fearless irreverence, which had defiantly answered critics in the wake of the Gucci Group’s acquisition (later becoming Kering), was now but a distant memory. McQueen’s resolute declaration, “It’s never become more commercial; it’s always been the same. Nothing affects me,” echoed through time.

True, McQueen championed the art of blending high and low, exemplified by the enduring McQ diffusion line. Still, it’s not hard to envision how a designer vehemently opposed to establishment norms and marketing hypocrisy would have grappled with the hyper-commercialization of his menswear and his eponymous brand. Notably, this brand had even ventured into the creation of Kate Middleton’s iconic wedding dress for the British royal wedding. Consider that in his lifetime, McQueen, a Scotsman who felt his homeland had been figuratively ravaged by England, boldly rejected a formal invitation from the Queen of England to dine with the Emperor of Japan. It’s a tale that fittingly fits the adage, “You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain.”